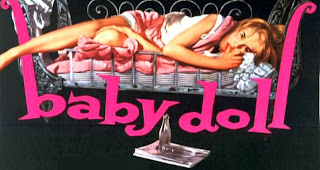

BABY DOLL : An American Satire

Although America is not a Catholic nation, a C rating discouraged families from seeing the film. It died quickly at the box-office, though the free publicity must have helped incite interest among some.

Tennessee Williams was the main force in the American theatre of the 1950s and a dominant force in films too. Many of his plays, with their controversial subject matter (including homosexuality), were quickly adapted to the screen, including A Streetcar Named Desire, The Rose Tattoo, Summer and Smoke, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Night of the Iguana, and (Williams' only novel) The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, to name a few.

Baby Doll, based on two earlier one-act plays by Williams, was the first time Williams had written directly for the screen. The result was even more scandalous than his stage plays, which had been sanitized (cleaned up) for the Hollywood screen. Streetcar and Cat, for example, had homosexual themes eliminated in their screen versions.

But a careful viewing of Baby Doll shows it's not about sex at all, despite the iconic image of Carroll Baker as "Baby Doll" in shorty pajamas, sucking her thumb in her baby crib. In fact, no sex occurs in the film, though sexual play is suggested.

Williams' film (as directed by Kazan) is obviously a satire on American sexual repression in the 1950s. Why not, since Williams, as a controversial playwright, had suffered more than most from that repression?

What better way to satirize American sexual repression than by showing an adult woman sleeping in a baby crib—a clear statement of the absurdity of denying sexuality to a young woman of twenty. Moreover, this woman is married!

Freud had taught that sexuality began in infancy (though "repressed," thus "latent" until puberty). But American society (dominated by Christian churches) continued to pretend that sex did not exist, unless in naughty girlie magazines or in the smutty minds of homosexual playwrights such as Mr. Williams.

In fact the American theatre openly explored sexual themes at the time, including William Inge's Picnic and Dark at the Top of the Stairs. Robert Anderson's Tea and Sympathy (1953), also directed by Kazan, addressed the issue of effeminacy and homosexuality.

But Williams used sex as a main metaphor in his plays, as here. By showing an adult woman sucking her thumb in shorty pajamas Williams mocks the myth of sexual innocence, especially since this woman is married. By showing the absence of sexual maturity in "Baby Doll" (her name says it all), Williams and Kazan satirically advertise her sexuality.

"Baby Doll" Meighan is a "baby" and a "doll." But the two words somehow add up to their opposite meaning. They tell not of innocence (as Americans intended in their daily speech) but of a provocative sexuality (as the iconic image of Baby Doll in her crib shows). So much the better if that image provoked outrage among religious groups responsible for that repression!

In effect, Williams and Kazan "deconstruct" sexual innocence, displaying it by denying it at every turn. Baby Doll's father insured his daughter's innocence by insisting she defer sexual favors until twenty (the way adolescents were to defer sexual activity until marriage).

This seems to tweak the nose of moralists who believed sex should be saved for marriage. Why not (Williams asks with sarcasm) save sex even after marriage?

Thus the crib becomes a satirical symbol, as if to say: "Here's your 'baby doll'! You want to deny sexuality in young women and pretend they're 'babies' and little 'dolls'? Here's what you get: a Baby Doll! You get the sex you denied."

Williams and Kazan go this one further. Not only is a married woman sleeping in her crib and not having sexual relations with her legal spouse, Archie Lee (Karl Malden), but her spouse is forced to become a Peeping Tom of his own wife!

The two images together (Baby Doll in her crib and the spouse peeping at her) sum up the problem with the social repression of sex, which makes sex pornographic instead of normal. To add salt to his satiric wound, Kazan shows the Peeping Tom accompanied by man's faithful companion: his dog. Indeed, it looks like they're both peeping together.

Similarly, the farcical "hide and seek" sequence between Baby Doll and Silva Vacarro (Eli Wallach) sends up (mocks) the "girlhood" of Baby Doll. For later, once aroused, Baby Doll wants to continue with what she assumed was sexual foreplay. But Vacarro insists he was only playing a child's game with her.

However the main point has been made. The house that denied sexuality in Baby Doll for the sake of a sexless "home," is now empty of everything except sexuality, which is in all the empty rooms and especially the attic (the architectural "climax" of the house).

Vacarro suggests Freud's "Return of the Repressed," by which what we unconsciously deny returns in persistent, and increasingly monstrous, form. Having denied sex in herself, Vacarro's every move arouses Baby Doll, such as in her funny line after Vacarro keeps switching flies off her: "Stop switching me, will ya?"

In this view, the staircase of her house becomes symbolic, as when Vacarro follows Baby Doll up the stairs. For Freud taught that ascending a staircase may be a symbol in dreams for sexual intercourse, with its mounting excitement.

Indeed, the "attic" (the highest part of a house) is the one place Baby Doll says she has never been; and it's in the attic that she is finally conquered: She signs Vacarro's affidavit while lying on a rickety beam and then, aroused, chases after Vacarro down the stairs.

Every viewer would know the game of hide and seek here was really a game of sexual seduction, or even foreplay. But by not showing sex, Williams and Kazan evoke a stronger (and more sinister) impression of sex in the viewer. As Freud pointed out, the "repressed" returns in distorted form.

However sex is not the main target of Williams' and Kazan's satirical barbs, which attack American middle-class (and capitalistic) values in general. For example, the film's narrative hinges on the loss of the furniture from Archie Lee Meighan's house, bought on time (that is, credit).

The absurdity of linking Baby Doll's deflowering with her twentieth birthday suggests that virginity, like consumer goods, has an expiry date. Moreover, that date depends on one's credit rating. In fact, Archie Lee vows to Baby Doll that he'll possess her on her twentieth birthday (in two days) because his credit is now good!

In fact, Baby Doll was "sold" by her father for a nice home with nice furniture, the way most marriages of the time were made. It's ironic, then, that the ideal marriage results not in a home, but in an empty house, with no furniture in it, except for the kitchen and the bedroom ("nursery"). These rooms, in fact, satisfy our two basic biological needs: food and sex.

The empty house is in fact a symbol of the emotionally empty American household of the time: all appearance, with nothing inside. For this reason, Kazan repeats several shots of the house, looking like a ghostly mansion. The caretaker of the house, Aunt Rose Comfort (Mildred Dunnock) is herself a dotty relic of a past age who can't even remember to light the stove and wanders about like a ghost.

The Italian interloper, Silva Vacarro, insists there are ghosts in the house and simulates their presence in a farcical sequence superbly directed by Kazan. At the same time, Vacarro explains that those ghosts are the mean-spirited emotions of the people who live in the house. Thus the "ghostly mansion," or empty shell of the house, is a symbol for the empty (even evil) spirits that reside there.

Kazan enjoys sending up (mocking) not only the house but the entire "plantation," with its broken down automobile and swing (which Baby Doll fears cannot bear the weight of two people) and its picturesque blacks (the "Negroes" of the "Old South").

Note too how Kazan mocks the romancing of middle-class America, which customarily took place in automobiles and on swings. Here the automobile (the great American symbol of romantic escape) is a wreck; another scene between Baby Doll and Vacarro takes place in front of pigs!

Baby Doll's idea of "fine manners" is not to eat pecan nuts cracked in Vacarro's mouth. Yet later she demurs and accepts the nuts.

The issue of racism, an issue that dominated the US in the 1950s, is also exposed here. Blacks seem more like statues than like people. One even sings an Afro-American Spiritual ("I Shall Not Be Moved") on cue.

These blacks are staged as still lifes. This mocks, not blacks, but the image of blacks in movies of the "Deep South."

Comically, Gone with the Wind is evoked in the final image of Baby Doll and Aunt Rose Comfort returning to their gutted home at the end of the film, where Scarlett O'Hara's "Tomorrow is another day" becomes Baby Doll's "We've got nothing to do but wait for tomorrow," wondering if she and her Aunt Rose will even be remembered tomorrow. While the last words are given to Aunt Rose, a feeble interjection: "Oh my, oh my. . . ."

The stylish melodramas of Douglas Sirk (especially Written on the Wind) are also evoked in the image of the falling leaves, which appear at the end of the film. At this point, Kenyon Hopkins' jazz underscore suddenly turns saccharine to suit melodrama's conventions.

Unfortunately, Baby Doll does not maintain its satiric focus throughout. In fact, the last half of the film seems more like a satire on the Method Acting that Kazan had spearheaded with his introduction of Marlon Brando in both the stage and film versions of Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire, which revolutionized acting, not only in Hollywood, but in England as well.

Several scenes directly evoke Kazan's previous films, as when Archie Lee, crying for his Baby Doll, evokes the iconic moment in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) when Stanley Kowalski (Marlon Brando) yells frantically for his Stella.

The other scenes look more like group improvisations, familiar in Method Acting workshops, than like coherent parts of a drama. They seem more like acting exercises than like a natural development of a narrative.

Only in the last few minutes, when Aunt Rose Comfort and Baby Doll return to their home amidst falling leaves does the film regain a satiric focus coherent with the first part of the film.

No comments:

Post a Comment